|

| |

|

| |

|

Japan’s only research laboratory that studies the black sea bream

|

| |

|

|

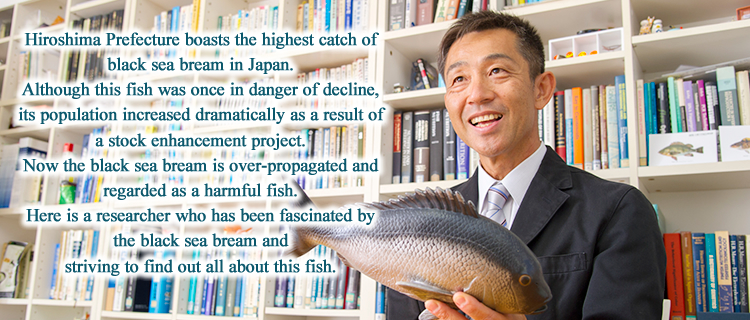

Professor Tetsuya Umino conducts research primarily on the ecology of the black sea bream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii). The Seto Inland Sea is main fishing grand to approximately 60 percent of the black sea bream landing in Japan. (or The black sea bream catch in Japan totals about 3,800 tons, 60 percent of which are caught in the Seto Inland Sea. ) The fish is called “chinu” in the Seto Inland Sea region.

Prof. Umino says that he decided to pursue his research career in this discipline because he has been very fond of black sea bream fishing since he was a junior high school student.

He says: “The black sea bream is considered one of the most difficult fish to catch, as exemplified by the fact that black sea bream fishing was incorporated as part of the training for warriors in the past in the Shonai district of Yamagata Prefecture. Due to this difficulty, various fishing methods have been developed, including fishing with watermelon or balled ground bait. Such a great variation in fishing methods can be seen only for the black sea bream.” |

|

| |

He recalls that he started to study the black sea bream because he thought that he could catch a lot more of this fish if he knew more about it. “Although now I know this is not always true in the real world, I have discovered two aspects about myself: on the one hand, I am a fishing lover, and the other hand, I am a researcher. I feel comfortable with my current status since I can see the black sea bream from these two different perspectives,” he says smilingly.

According to Prof. Umino, there are still many things that are unknown about the black sea bream. Moreover, only his laboratory carries out studies on this fish.

He adds: “Unlike studies on marketable fish species, for which a research grant is easier to receive, it is difficult to obtain a grant for research on the black sea bream. Accordingly, everyone stays out of this research, so that now we are unrivaled in this discipline.”

In addition, there are more than enough populations of the black sea bream, which constitute its greatest strength as a research subject. Capitalizing on this advantage, Prof. Umino’s laboratory continues to study the black sea bream using a variety of methods. |

|

|

|

| |

|

Hoping to resolve all mysteries about the black sea bream, his research activities have expanded to include making useful proposals to fishermen

|

| |

|

|

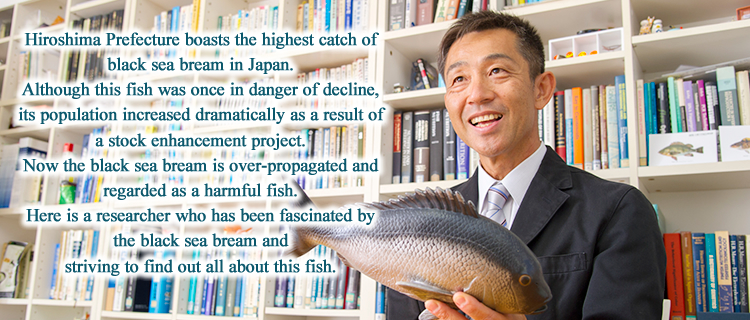

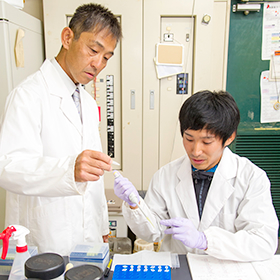

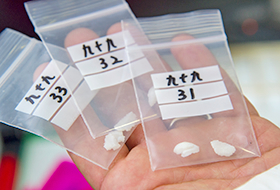

Specifically, his laboratory carries out research, by such means as analyzing collected samples and tracing a black sea bream tagged with an ultrasonic pinger to investigate its migration route on a real-time basis. In this manner, the laboratory members use various techniques to explore the ecology of this fish. Survey items are wide-ranging, including the ages of black sea bream, its genetic information, what the fish eats, how long it takes for the fish to grow up, when and where it spawns, and how long it lives.

Prof. Umino states: “Our research results have shown that much of what has conventionally been said about this fish by people who like fishing is wrong. For example, the black sea bream has been thought to have good eyes, but it has poor eyesight in reality. Also, although many people believe that this fish lives in the deep sea, it actually highly prefers shallow waters.”

Thus far, his laboratory has made many discoveries like this. However, he says that “the more we conduct research, the more we encounter questions.”

Prof. Umino talks about his future vision smilingly: “While I am alive, I want to obtain as much information as possible, so as to fill in the missing pieces of the puzzle. My dream is to pursue studies to clarify all of the mysteries of the black sea bream as my life work.” |

|

| |

Additionally, his laboratory works on activities that bring about benefits to fishermen. The black sea bream is regarded as a harmful fish because it eats juvenile oysters and clams growing in the Seto Inland Sea. Prof. Umino is considering measures to reduce this damage somehow.

He explains: “For example, wild spats of oysters are planted around June, corresponding to the spawning season for the black sea bream. Since the fish has an increased appetite during this season, we recommend fishermen to plant oyster spats around March, when the water temperature is low and the black sea bream is less active. We also advise fishermen to keep a greater distance between the collectors (scallop shells) with planted spats and the farming rafts for adult oysters, since the black sea bream will soon come close to these rafts if the collectors are placed at their side. In this manner, we provide fishermen with useful information.”

Recently, there has been a move to reconsider the black sea bream as a local resource, and discussions have been held as to the regeneration and reuse of the black sea bream, according to Prof. Umino.

He also shows his enthusiasm, commenting: “It is very nice to see such a move. I would also like to come up with various ideas to facilitate the move, based on the outcomes of our black sea bream research.” |

|

|

|

| |

|

A rare type of researcher, who heads a laboratory that is full of a sense of enjoyment

|

| |

|

|

|

His research subjects are not limited to the black sea bream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii), but include the oval squid (Sepioteuthis lessoniana), rockfish (Sebastes cheni), and sweetfish (Plecoglossus altivelis altivelis). However, it is safe to say that he is second to none as a specialist in research on the black sea bream. He decided to become this type of researcher for the following reason.

Prof. Umino states: “I think nowadays the scope of a researcher’s perspective is considerably narrow. In many cases, research fields are so splintered that only one method is used to investigate multiple different species of fish. While there are many researchers who possess tremendous knowledge about a certain discipline, fewer and fewer researchers have the knowledge to explain everything about a single species of fish.”

“Taking a holistic approach enables us to see the entire picture. If I could impart this knowledge to my students, this would make them happy as well as myself. Although it may go against the times, I have been striving to be such a rare type of researcher,” he adds.

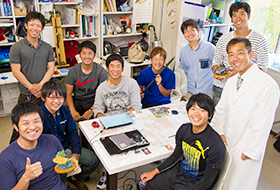

Prof. Umino says that his laboratory has attracted many excellent students.

“My students are fun-loving and often enjoy fishing, but actually they study very hard as well. Students with high grades often become members of my laboratory. Since my laboratory is highly indicative of the concept ‘Study Hard and Play Hard,’ I ardently hope that those wishing to enjoy their college life in line with this concept will join my laboratory.”

With a smile on his face, he says, “I am happy to be surrounded by nice people.” For Prof. Umino, Hiroshima University offers an ideal research environment. After graduating from the university, he first worked at a major private company. However, in response to the invitation from a senior researcher who likes fishing, he started to pursue a career as a researcher. This must be an indication that God has called upon him to engage in research on the black sea bream.

“I often say that while I am catching black sea bream, it is actually the fish that is catching me. I think that, just like me, continuing to study a fish, even if it is an inconspicuous species, will lead to positive results. I recommend students to find something they like and work hard on that subject with a strong wish to know all about it. Then the research results may contribute to the betterment of society,” says Prof. Umino. |

|

| |

| Tetsuya Umino |

Professor

Laboratory of Aquaculture

January 1, 1991 – April 30, 1999 Research Assistant, School of Applied Biological Science, Hiroshima University

May 1, 1999 – March 31, 2006 Associate Professor, School of Applied Biological Science, Hiroshima University

April 1, 2006 – Associate Professor, School of Applied Biological Science, Hiroshima University

April 1, 2018 – present Professor, School of Applied Biological Science, Hiroshima University

Posted on Jan 15, 2016

|

| |