|

| |

|

| |

|

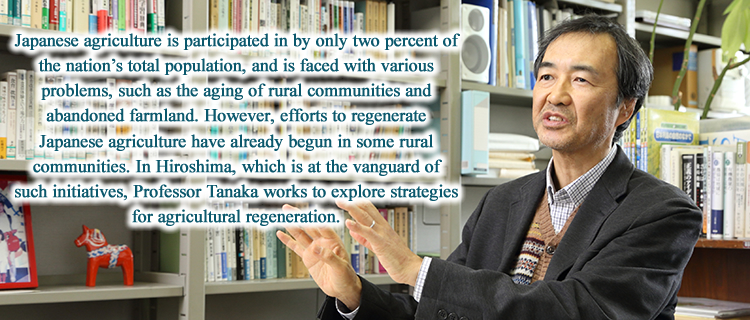

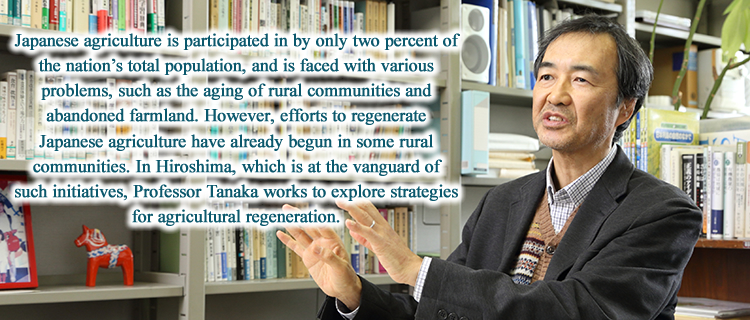

Studying agriculture in Hiroshima Prefecture, which is taking the lead in

efforts to regenerate Japanese agriculture

|

| |

|

|

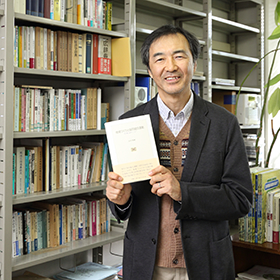

Professor Tanaka’s professional career as a researcher may be

somewhat unusual. Originally his interest in consumer education led him to

research cooperative societies at the School of Education, Hokkaido

University. Next he worked as a full-time researcher at the Japan Life

Safety Research Center & CCW and at the Consumer Co-operative Institute

of Japan. He became known as a pioneering researcher of cooperative

societies. Subsequently he moved to Hiroshima University. Since then he has

studied agriculture, in the course of which his subject of study has shifted

to Japan Agricultural Cooperatives, or JA.

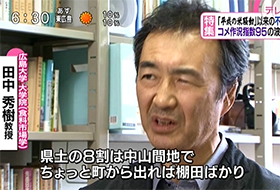

“Now I am working on research concerning agriculture in Hiroshima

Prefecture. Hiroshima is a so-called disadvantaged prefecture, and is

considered to be at ‘the leading edge of the decline of Japanese

agriculture’,” says Professor Tanaka. Agricultural communities in Hiroshima

Prefecture are aging faster than in any other prefecture in Japan, and its

agricultural population keeps on decreasing. Under such circumstances,

nevertheless, various initiatives are under way, so that expectations are

growing that, conversely, Hiroshima Prefecture may be becoming a

“frontrunner for the regeneration of Japanese agriculture.” |

|

| |

According to the professor, the key to the regeneration of

Japanese agriculture lies in a new style of practice called “community

farming.” He says that “To be more accurate, this is what is referred to as

an ‘agricultural production corporation.’ At present, Hiroshima Prefecture

has more than 200 agricultural production corporations, which is the largest

number in Japan.”

Professor Tanaka explains the reason why this change occurred, saying that

“When it comes to cooperative society regarding agriculture, many Japanese

people think of the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives. However, more and more

Agricultural Cooperatives have been merged into larger-scale entities.

Agricultural Cooperatives in Shimane Prefecture will be integrated into a

single entity. In Hiroshima Prefecture, currently there are 13 JA

cooperatives. Europe is far ahead of Japan. European agricultural

cooperatives have been merged and become incorporated as companies,

transcending national boundaries. In Europe, the process of incorporation

has progressed, because farmers require agricultural cooperatives to be more

profitable, as farmers became larger and assume the characteristic of

enterprises. In contrast, in Japan, many farmers have side jobs, and

generally their agricultural operations are small in scale, with the aging

of rural population accelerating. In addition, agricultural cooperatives in

Japan are mainly focused on providing credit, which is no longer required by

elderly farmers. Against such a backdrop, new forms of cooperative

organizations have come into existence.” |

|

|

|

| |

|

Considering a better form of agriculture by reviewing the present situation

of community farming

|

| |

|

|

He states that for Japanese farmers, “community farming” is a

more familiar style of cooperative organization that replaces the

conventional agricultural cooperatives. Behind this are truly serious

issues.

“Farmers in Japan are in possession of farmland that has been handed down

from generation to generation, and they are reluctant to sell it to others.

However, it is difficult to maintain the farmland if current conditions

remain unchanged. Also they have no successors. One of the methods to wisely

resolve these issues is ‘organizing an agricultural network,’ in other

words, establishing agricultural production corporations,” explains

Professor Tanaka.

The mechanism is as follows:

Farmers continue to hold the farmland ownership rights, but entrust only the

right of land-use to an agricultural production corporation. Then the

cooperation can save costs, since it can collectively manage several tens of

hectares of land. On the other hand, farmers are very grateful that the

corporation collectively undertakes rice paddy-related work, from rice

planting to harvesting. |

|

| |

Notably, many farmers in Hiroshima Prefecture do not want to be in a state

that they just own their farmland but engage in no agricultural practices by

fully entrusting faming work to the corporations. Rather they seek to

participate as much as possible in the management of their farmland,

including paddy water management and vegetable cultivation in plowed fields,

as part of their efforts to make agriculture viable in the entire local

community.

Professor Tanaka added that “The operators’ group of the corporation is in

charge of operating farm machinery, while farmers try to remain involved in

agriculture as much as possible they can. This is a model for the current

agricultural production corporations. I am committed to this research while

envisioning that a new Japanese agriculture is being developed in this

prefecture that is at the vanguard of the nation’s agriculture.” |

|

|

|

| |

|

Looking at the future of Japanese agriculture through comparison with

Europe

|

| |

|

|

|

Technically speaking, the farming populations should be

differently named according to the operation scale. They are “farmers (who

manage large-scale farms)” more often in the United States, whereas

“peasantry (small farmers)” are found more frequently in Japan and Europe.

Professor Tanaka points out that when considering the agriculture of Japan,

comparing it with that of European countries to identify the differences

will help us to understand what we cannot understand when looking at only

Japan.

He analyzes saying “In Japan, at least water-rights communities, i.e.,

villages are maintained even now. However, in Europe, old village

communities were broken up in the modern period. For this reason,

agricultural operations could be individually completed and could grow

larger on an individual basis, so that a considerable number of peasants

effectively became farmers. In Japan, the peasantry is maintained somehow or

other, although becoming partly collapsed. Accordingly, there are

differences in the cooperative organizations of the farming populations

between Japan and European countries.” The professor intends to continue

various comparative studies so as to consider the future of Japanese

farmers.

Recently agricultural production corporations in Japan have been

enthusiastic about not only agriculture but also other businesses, and

making regional contributions by such means as providing shuttle-bus

services, setting up direct sales stores, and running supermarkets and gas

stations. To our great surprise, these activities have resulted in the

creation of new jobs and employment opportunities, thereby

retaining/attracting more young people in/to the local communities,

according to the professor.

Professor Tanaka stated that community farming is very interesting in that

it has organized networks of the farming population, while keeping them

engaged in agricultural practices. I consider it significantly important

that farmers find such solutions by themselves.” He added with a smile that

“It is intriguing to observe diversity in the forms of agricultural

production corporations in respective communities. In the future, I wish to

further expand this research, from the analysis of the present situation to

the prediction of the future direction of farmers. I would be very happy if

our research findings could be of help in shaping a better future for

agriculture.”

Higashi-Hiroshima City, where Hiroshima University is located, has the

largest agricultural production corporation in the prefecture. The

corporation was established by a former agricultural extension worker in

Hiroshima Prefecture who earned a master’s degree in Professor Tanaka’s

laboratory. Moreover, in Higashi-Hiroshima City, activities have been

vigorously under way to form associations of agricultural production

corporations, an example of which is Farm Support Higashi-Hiroshima. These

activities attempt to encourage several corporations to fund and jointly

establish another new corporation, in which agricultural machines will be

concentrated to achieve even higher efficiency. These machines are used in

turn by the participating corporations.

Professor Tanaka concludes that “I feel extremely grateful that I can

witness these examples around us. Whenever I examine the present situation

in person, I can well understand that all participants are truly

enthusiastic and devising various ideas. By making detailed observations of

their practical activities, we will further push forward with research as to

“organizing an agricultural network.” |

|

| |

| Hideki Tanaka |

Professor

Laboratory of Agricultural Marketing

April 1, 1988 - September 30, 1989 Full-time Researcher, Japan Consumer Research

Institute

October 1, 1989 - March 31, 1990 Full-time Researcher, Consumer Co-operative Institute

of Japan

April 1, 1990 - October 15, 1992 Research Assistant, School of Applied Biological

Science, Hiroshima University

October 16, 1992 - March 31, 2000 Assistant Professor, School of Applied Biological

Science, Hiroshima University

April 1, 1995 - March 31, 1996 Visiting Research Fellow, Swedish University of

Agricultural Sciences (Sweden)

April 1, 2000 - present Professor, School of Applied Biological Science, Hiroshima

University

Posted on Apr 3, 2015

|

| |