|

| |

|

| |

|

Performing basic research to comprehensively understand the mechanisms behind mammalian ovulation and insemination

|

| |

|

|

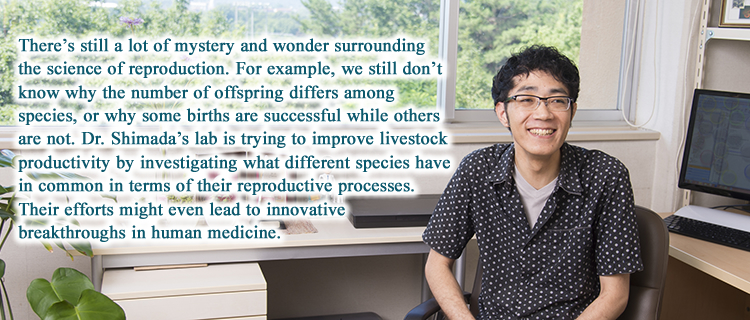

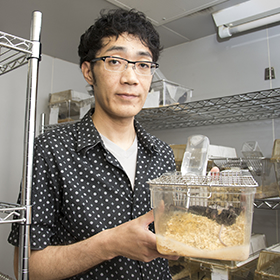

A specialist in reproductive biology, Dr. Shimada runs a lab that is currently studying the biological and molecular mechanisms behind ovulation and fertilization using genetic-targeted mutant mice model.

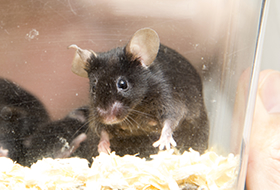

“The number of pups per delivery differs among species. Cows generally give birth to only one offspring, while mice give birth to about ten. Selectively bred pigs can produce litters of more than 20 progeny. This all depends on how many oocytes are ovulated and then fertilized.

We still don’t know how to regulate ovulation and fertilization. The number of offspring relies on how many oocytes are ovulated from the ovary. Our lab is currently attempting to elucidate the mechanisms that regulate the process of ovulation and fertilization.”

|

Dr. Shimada has been studying reproductive biology for 15 to 16 years. He started his work from his graduate study using pig oocyte model. However, we’re now using genetically modified mice. We adopted the mouse model to large animal and also human model, because it provides us with direct evidence of what happens when certain genes are knocked out.”

Dr. Shimada gained the idea of using mice from American endocrinologists, Professor, JoAnne S. Richards, PhD, Baylor College of Medicine, he worked with her in the U.S. during an overseas fellowship funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

“My current approach consists of integrating my existing knowledge of swine and bovine models with basic research using the mouse model, and applying the results to livestock in general.

|

|

|

Our lab employs molecular endocrinology to analyze genetic mechanisms, and we believe we’re performing some of the most cutting-edge research in this field in the entire world.”

|

|

|

Earning patents for a technique to artificially inseminate swine using frozen semen

|

| |

|

|

Dr. Shimada is also famous for developing a technique to artificially inseminate swine with frozen semen.

“Artificial insemination of cows with frozen semen is now a routine process done everywhere, but with pigs the proliferation rate has been about 0%. This is because the definition of successful reproduction differs between the two species. In the case of cows, your goal is to produce one offspring so your probability of success is 50%. In other words, it’s a win or lose situation. In the case of pigs, however, you win if you produce a litter of ten or more, and lose if your sow does not become pregnant. But then, if you manage to produce three or four offspring you find yourself with something akin to a draw. Moreover, the order of preferred outcomes does not go from win-draw-loss; instead, it goes from win-loss-draw, with a draw being the worst result.

|

This is because a litter of only three offspring from a sow that had been pregnant for 120 days and possessed the potential to deliver ten newborns presents a loss in productivity. A failed pregnancy would have been a better result because you could have immediately tried to inseminate the sow again.

|

Frequent draws indicate poor efficiency and this is why artificial insemination of pigs with frozen semen has not proliferated at all.”

The artificial swine insemination techniquejointly developed by Dr. Shimada’s research group and the Oita Prefectural Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Research Center achieves a pregnancy rate of 80% and an average litter size of 10 offspring.

This ground breaking technique has led to the approval of multiple patents and the establishment of a university-based startup. Moreover, it is now being employed widely in the agriculture industry.

Dr. Shimada believes his lab has a social responsibility to spread such fruits of their research.

|

|

|

“I think it’s very important to give back to society through university research, to contribute to humanity through our work. I feel I’ve done something worthwhile when I hear voices of delight from agricultural producers.”

|

|

| |

|

Taking a unique approach to understanding the entire reproductive system

|

| |

|

|

|

“We’re concurrently studying female mice and male swine because we believe their biological mechanisms have much in common in terms of the reproductive cycle. We’re committed to continuing this kind of synergistic research because we know there will be things we will invariably overlook if we perform such studies on an individual basis,” says Dr. Shimada.

Dr. Shimada’s ultimate goal is comprehending the entire reproductive system. Doing so will reveal the causes of reproductive disorders in livestock, which in turn may lead to the development of treatments for infertility in humans. Some lab alumni are actually working on fertility problems at hospitals .

In the course of realizing this goal, Dr. Shimada also wants to foster competent young scientists with leading-edge technological skills and knowhow.

“If we continue to embrace unique research perspectives and approaches, those who worked with us will eventually be recognized as alumni of the Shimada Lab at Hiroshima University. In this sense, I want our lab to develop an original personality that it can call its own.”

|

Hiroshima University is a place where you can create your own possibilities. Students are able to pursue their ambitions by transcending departmental boundaries and collaborating with specialists in various fields. I hope students who study here will go beyond their individual areas of expertise and become scientists with knowledge and experience in a wide range of disciplines.”

|

|

| |

| Masayuki Shimada |

|

Associate Professor

Laboratory of Animal Reproduction

April 1, 2000 to March 31, 2002:

Research Associate, School of Applied Biological Science

April1, 2002 to March 31, 2006:

Research Associate, School of Applied Biological Sciences

April 1, 2006 to present:

Assistant Professor, School of Applied Biological Sciences

April 1, 2007 to present:

Associate Professor, School of Applied Biological Sciences

Posted on Oct 18, 2013

|

| |