|

| |

|

| |

|

“You are wasting taxpayers’ money!” His mother’s harsh words

motivated him to extensively explore ways to determine the maturity of fruits without

cutting them.

|

| |

|

|

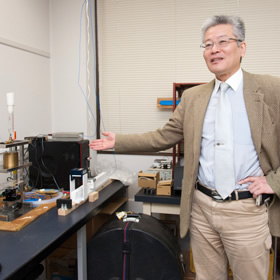

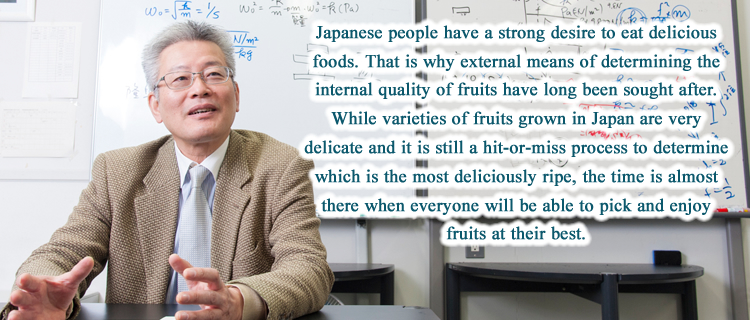

Professor Sakurai specializes in plant physiology, a discipline

that studies the growth and development of plants. His most noted

research concerns the “development of nondestructive methods of

measuring fruit quality.”

Several methods of checking the ripeness of fruits have

been introduced so far. Initially, these methods assessed only sugar

content through image analysis or near-infrared spectroscopy. These

conventional means, however, were limited in that they were not

applicable to varieties that do not let light through and that they

were incapable of sorting out overripe fruits. Meanwhile, it has

been known since olden times that firmness is one of the reliable

criteria for determining whether a fruit is ripe for the picking. In

fact, it has long been a routine practice for fruit farmers to put a

stick into the flesh of fruits to check their ripeness. Besides,

according to Professor Sakurai, Japan is the most meticulous of all

fruit producing countries in terms of fruit quality assessment

“That is a reflection of Japanese consumers’ enthusiasm

about eating delicious foods,” says the professor. And that is why

there has been a need in this country for even more effective means

of fruit quality assessment.

|

About 20 years ago, Professor Sakurai went to the U.S. to

conduct research on tomatoes and learn various relevant techniques for a

period of one year. His destination was UC Davis in California. The

university conducted numerous studies on tomatoes because the UC Davis

campus was located in the middle of a major tomato producing area that

represented a quarter of the volume of tomatoes processed worldwide.

While in the U.S., Professor Sakurai was asked to

physically assess the maturity of tomatoes. So he cut tomatoes, stuck a

needle into their flesh, measured the resistance that was generated, and

organized numerical data obtained to produce a scientific paper. On his

return home, he exultantly told his mother about his accomplishment in

the U.S. However, his mother sniffed at his story, saying, “I’ve already

known about your ‘findings’ because I cut tomatoes every day. It is a

sheer waste of taxpayer’s money to put into those difficult figures what

you can clearly see just by cutting tomatoes!”

Determined to impress his mother next time around,

Professor Sakurai embarked on a new research project.

|

|

|

|

|

An encounter that resulted in the development of a “nondestructive”

technique for assessing the ripeness of fruits from their firmness

|

| |

|

|

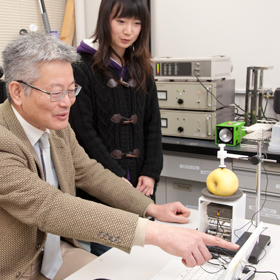

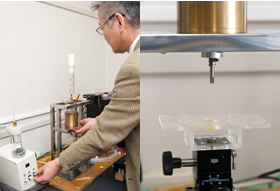

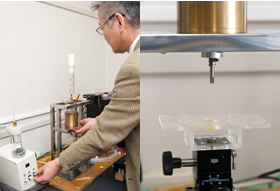

Guided by the intuition that the “sound” may be the key

parameter, Professor Sakurai started an experiment in which the

sound of various frequencies was applied to fruits so the fruits

could “hear” it and the sound waves that passed through the fruits

were received with a microphone.

Based on his findings, Professor Sakurai wrote several

papers, but he was somewhat uncomfortable about continuing that

research project. At the time he almost decided to end the project,

he was spoken to by a person from a certain company during an

academic society’s poster session.

When that person asked “What are you interested in

doing?”, Professor Sakurai explained about his research interest.

The person responded, “Maybe we can help you. I will send you

documents after I get back to my company.”

After a few days, Professor Sakurai received a bundle

of documents several centimeters thick. Some documents suggested

that it might be the vibration rather than the sound that is the

key. A brochure concerning vibration measuring devices was also

attached. This was the professor’s first encounter with the laser

Doppler vibrometer.

|

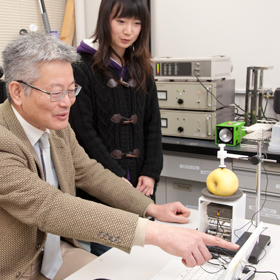

When given a vibration, any object resonates with a unique

resonance frequency. Using this rule, one can determine firmness and

maturity of fruit. Because the formula necessary for the procedure had

already been developed by a physicist many years ago, all one had to do was

apply the obtained data to the formula. Convinced of its potential,

Professor Sakurai embarked on studies of this technique somewhere around

1994. For nearly 20 years since then, he has been engaged in research on

this method.

“This vibration technique is a good means of collecting

internal information from living things,” says the plant physiologist.

Although vibration technology itself is advancing day by day, its

application to fruit is unprecedented and Professor Sakurai is the world’s

first scholar to refine fruit quality assessment procedures using vibration

technique to this extent.

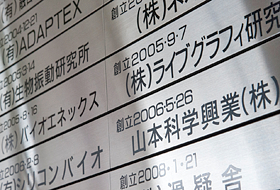

In 2005, based on his research results, Professor Sakurai

founded Applied Vibro-Acoustics Inc. (AVA) in Hiroshima University’s Venture

Business Laboratory. In the ensuing year, in cooperation with a professor

who is also his senior researcher, the plant physiologist established

Yamamoto Kagaku Kogyo Inc., a company engaged in the development of a small

device that has the same level of precision as the laser Doppler vibrometer.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Aspiration to see the laser Doppler vibration promote Japanese agriculture

and lead to the establishment of “Japan Brand”

|

| |

|

|

Asked about the joy of his research, Professor Sakurai says, “The

most exciting part of it is to hear from someone about specific ways

in which the techniques I developed are helping him or her. It is

indeed a pleasant surprise to find that these techniques are being

used for various unpredictable purposes. I really enjoy working in

my lab every day, measuring many different things.”

Furthermore, the professor continues, “One of these

days, we will have kiwifruits, avocados, and a number of other

fruits on supermarket shelves with ‘Best Period to Eat’ labels,

showing shoppers specific dates on which these fruits become most

delicious. Also, fruits such as watermelons sorted and bred using my

vibration technique may be distributed in the market someday, though

such application is invisible. In the years to come, I would like to

work on the La France pear and other fruits whose smells and colors

do not help at all in determining their maturity.” Given the

professor’s strong commitment to his research, we may have a chance

to see the “fruits” of his endeavors with our own eyes in the

not-too-distant future.

Professor Sakurai’s methods will also help establish

“Japan Brand” and promote agricultural exports. “If we can determine

when a fruit will be at its best, we will be able to reduce losses

and increase consumption, thereby rewarding producers for their

efforts. It is my hope to build that kind of mechanism and

contribute to ‘aggressive farming.’”

|

|

| |

| Naoki Sakurai |

Professor

Evaluation of Plant Environment Laboratory

Hiroshima University School of Applied Biological Science

August 1, 1980 – September 30, 1988: Research Associate, School of Integrated Arts and

Sciences, Hiroshima University

October 1, 1988 – March 31, 1993: Associate Professor, School of Integrated Arts and

Sciences, Hiroshima University

April 1, 1993 – March 31, 2006: Professor, School of Integrated Arts and Sciences,

Hiroshima University

April 1, 2006 – Present: Professor, Hiroshima University Graduate School of Biosphere

Science

Retired on March, 2016

|

| |