|

| |

|

| |

| A fishing lover who has become a researcher of annelid worms aims to farm them and clarify their life history |

| |

|

|

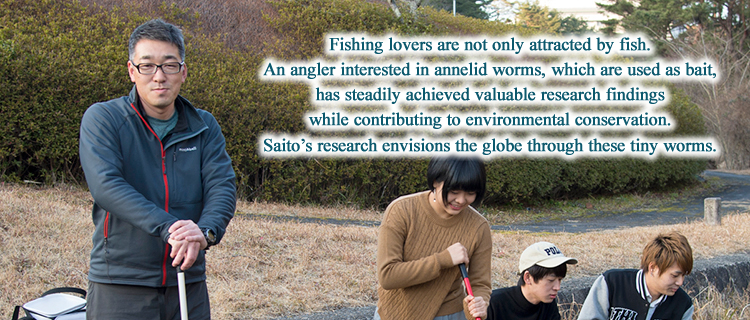

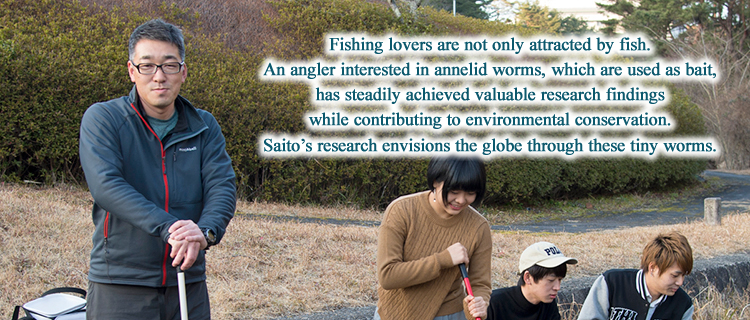

Research activities by Associate Professor Saito focus on the ecology of annelid worms, which are used as fishing bait, as well as other benthic animals including shrimps and crabs. According to Saito, there are few researchers studying bristle worms in Japan. While these worms are sometimes used as environmental indicators, nobody has specifically specialized in the study of worms used as fishing bait. However, Saito was such an enthusiastic fan of fishing that he had already determined to study annelid worms before selecting a university to enter. While he was at Nagasaki University, Saito mainly classified small one- to two-centimeter-long annelid worms into groups. However, what he really wanted to do was conduct research on the farming of larger annelid worms that could be used as fishing bait. Saito looked for a laboratory where he could undertake the research that he really wanted to do, and decided to proceed to the School of Applied Biological Science of Hiroshima University.

“At present, fishing baits used in Japan are mostly imported from other countries. Although we used to be able to catch baits in Japanese seas, such catches have been steadily declining, and now baits are imported from China and South Korea. I wanted to realize their farming through research. This was my starting point,” says Saito. |

|

| |

As Saito proceeded with his research, he was increasingly interested in the ecological aspects of worms, and wanted to clarify their life history including their feeding and breeding behaviors. The scope of research further expanded to the polychaete Halla okudai, as well as lancelets. In his doctoral course, Saito focused his research on clarifying the feeding behavior of the polychaete Halla okudai. Subsequently, he has undertaken a broad range of research activities to clarify the life histories of the target animals.

“Recently, I have returned to fishing baits, and have conducted research activities regarding annelid worms and other animals in relation to non-native species.”

Over the past 10 years or so, the issue of non-native species has been highlighted, whether terrestrial or aquatic. This issue is also significant with aquatic animals, which are the targets of Saito’s research. |

|

|

|

| |

| Having received high evaluation for his status survey report on imported baits, Saito is also proactively improving awareness of such baits among anglers. |

| |

|

|

“In media coverage of the issue of non-native species, it is reported that only two or three species are imported as fishing baits. However, the actual number of species imported as baits is much larger,” states Saito. Because no practical surveys had been conducted on the actual status of such baits, Saito started to conduct surveillance in around 2009. He published a paper in 2011 summarizing the results of the surveillance; this paper is so highly evaluated that it is still quoted in many fields. Such an achievement could only be made by Saito, with his sheer love for fishing and his knowledge and experience of classification.

Associate Professor Saito says that he has two major goals in his future as a researcher. The first is to clarify the life histories of as many species as possible that he has handled. The second is to disseminate the issue of non-native species used as fishing baits to the general public. |

|

| |

“With respect to the issue of non-native aquatic species, reports have mainly been made concerning the discharge of ballast water during marine transportation, and seeds for aquaculture. Other factors have rarely been investigated. This is why I conducted these surveys. However, a larger problem existed among anglers.”

Saito continued to share with us an incredible truth.

“The habit of anglers of discarding their remaining bait before going home?this is intricately connected to the issue of non-native species.”

Many anglers discard their bait at the fishing site, to avoid the trouble of taking them back home, out of pity for the bait animals, or because they hope the fish will grow larger by consuming that bait. At present, this behavior is not prohibited by law, and is rarely criticized as a breach of etiquette. However, such behavior could result in the breeding of the bait animal at the site, transforming it into a non-native species. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

“Most people discard bait without thinking that far. Because the population of anglers is 50 times greater than that of professional fishers, the impact of their behavior is far from negligible,” fears Saito.

“Even clerks at fishing tackle shops often don’t know this. Therefore, I would like to improve recognition among the general public by publishing my research results.” Associate Professor Saito hopes to return the benefits of his research to society in this way. |

|

| |

| Finding what you have looked for is the best part of our research; pursue something you can be the best at! |

| |

|

|

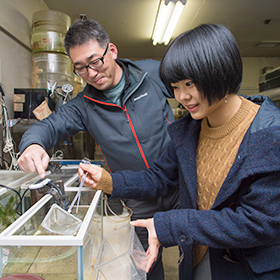

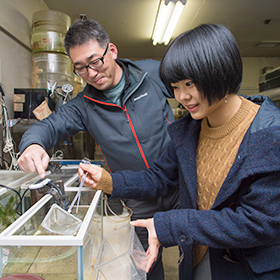

As mentioned earlier, Saito’s research scope includes lancelets, which are peripheral to the annelid worms at the center of his research. He has jointly conducted the research on lancelets with a previous professor of this laboratory and with Professor Kawai. Lancelets have drawn interest in terms of evolutionary biology, as an animal straddling the boundary between vertebrates and invertebrates, and in terms of being a symbol of environmental conservation, as a rare species with substantially reduced habitats due to sea sand collection and other activities since the 1960s.

“In Japan, there had been concerns about the preservation of lancelet populations in their habitats, including Uryujima Island in Hiroshima Prefecture, and Mikawa Oshima Island in Aichi Prefecture, which are designated as natural monuments by the Japanese government. We conducted a survey on board the Toyoshiomaru, a training ship of Hiroshima University, and found several habitats in the Seto Inland Sea.” Subsequently, Saito has undertaken research activities not only to clarify the life history of lancelets, but also from the viewpoint how the oligotrophication of the Seto Inland Sea is related to the animal’s habitat density.

According to Saito, students who enter his laboratory ‘love fieldwork’ in general. “Our research mainly consists of fieldwork. Before we set out, we formulate survey plans to determine the approximate locations of the animals. The most exciting times are when we find the target animal in the exact location that we anticipated, when we find a larger population than expected, or when we collect the animals we find.”

In conclusion, Associate Professor Saito sends out the following message to young people who want to become researchers.

“I hope that everyone will aim to become the ‘only one’ researcher of any animal that they know and study it better than anyone else. No matter how small, pursue something you can be the best at, and make it the basis of your self-confidence.” |

|

| |

| Hidetoshi Saito |

| Associate Professor, Laboratory of Aquatic Ecology

August 1, 1997-March 31, 2007 Assistant, School of Applied Biological Science, Hiroshima University

April 1, 2007-October 31, 2012 Assistant Professor, School of Applied Biological Science, Hiroshima University

November 1, 2012-present Associate Professor, School of Applied Biological Science, Hiroshima University

Posted on Jul 14, 2017

|

| |