|

| |

|

| |

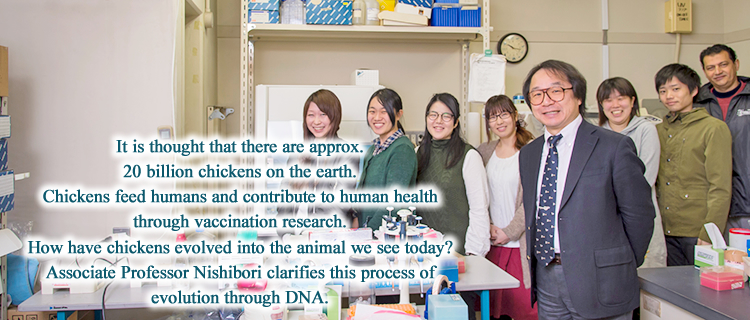

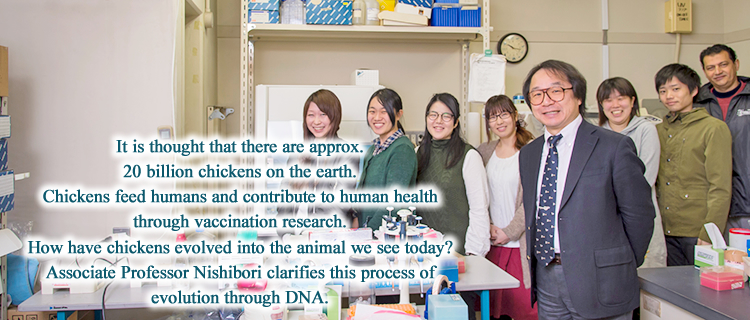

| Two pillars of research: how chickens have been domesticated as livestock, and

what ingredients are contained in food products made from livestock chickens |

| |

|

|

Professor Nishibori belongs to the Animal Breeding and

Genetics Laboratory, which undertakes research into the genetics of chickens and

various other animals. Nishibori’s research in this laboratory has two pillars.

One is research into how wild chickens have been domesticated as livestock. The

other is an approach to identify ingredients contained in food products made

from livestock chickens.

“We use a method called ‘DNA analysis’ for both of these research pillars. The

former pillar is research concerning domestication, and investigating the

process of how chickens have been domesticated. The latter pillar is an approach

for clarifying meat ingredients that should not be naturally contained in food

products, and that could raise allergic or religious issues,” tells

Nishibori.

“The chicken is the animal that would be the most difficult for humans to

dispense with. On the other hand, the chicken has become the least familiar

livestock animal in our everyday lives.” |

|

| |

Nishibori says that there are so many kinds of chicken products

around us that, if chickens disappeared, no convenience stores could survive,

and riots would break out in Western Asia. In fact, there was a case in Mexico

where the spread of avian influenza resulted in a riot. In the past, there used

to be no large-scale spreads of avian flu as we see today. Nishibori suspects

that this elevated susceptibility to avian flu must have caused by a change that

occurred due to the breed improvement of chickens.

“It is expected that clarifying the history of the domestication of chickens

could lead to the resolution of these problems, and be applied to breeding and

various other aspects of chicken research.”

Nishibori points out that chickens are no longer kept in the yards of private

houses, as a countermeasure against diseases, and that this is why opportunities

to see chickens have substantially decreased. This is associated with another

aspect of chicken research, as described later. |

|

|

|

| |

| Ambitious goal to clarify the gene flows of various animals |

| |

|

|

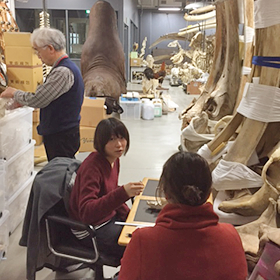

Chickens originated in Southeast Asia and spread around the world.

In his research into the process of domestication, Nishibori aims to clarify the

gene flow for the spread of chickens, by using DNA information on the one hand,

and by physically observing local chickens on the other.

“We call this a ‘chicken world exploration project.’”

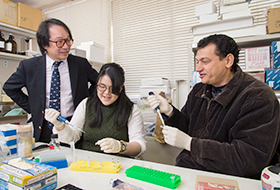

While many laboratories for DNA analysis conduct their research indoors,

Nishibori’s laboratory emphasizes physical observation, and takes students to

other countries as frequently as possible, so that they can observe the actual

lives of livestock with their own eyes, and collect and analyze samples with

their own hands whenever possible. |

|

| |

“Doing so provides us with a strong sense of fulfillment. We can

feel that we are analyzing that individual chicken that we observed at that

time. This physical observation and recognition enhances our motivation,”

remarks Nishibori.

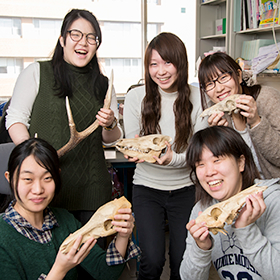

This approach is not limited to chickens, but is also applied to pigs, camels,

and even an endangered species called the “saiga antelope.” Nishibori’s team

visits Okinawa every year to research a pig bred from wild boars. They also

promote joint research of saiga antelopes with Kazakhstan. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

“The saiga is a kind of antelope. It is a little-known animal with

an elephant-like trunk. We conduct research on how to preserve this critically

endangered species. There used to be around 100,000 saiga antelopes, but the

population suddenly dropped to 20,000 at a stroke. As part of the investigation

into the cause of this sudden decline, we performed DNA analysis on the family

relationships of the surviving saiga antelopes. This analysis clarified that the

surviving antelopes were not genetically akin, and therefore no problems would

result from conserving the surviving antelopes as they were.”

Nishibori also undertakes joint research on sunfish with marine biologists,

suggesting his ever-expanding scope of interest. |

|

| |

| Has been practicing the development of next-generation researchers for 15 years;

his motto is “What you like, you will do well.” |

| |

|

|

|

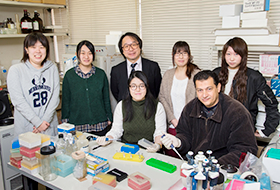

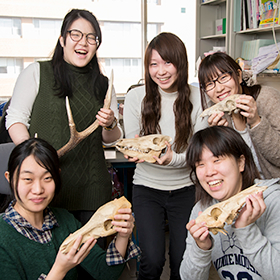

Nishibori is well known among high school students. On a request

from a prefectural high school, he started, about 15 years ago, high

school-university cooperation for students in science and mathematic courses.

For about 10 years, he has also participated in, and given catered lectures at,

programs and events including “Hirameki Tokimeki Science (innovativeness &

excitement of science)” for elementary school, junior high school, and high

school students, organized by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science;

and “Yumenavi Live,” organized by FROMPAGE and sponsored by the Ministry of

Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. His lectures are always

entertaining, easy to understand, and therefore become popular. Nishibori has

received many awards for these activities.

“The most exciting times are when I find something new, and when I communicate

what I am doing to many people. This is why I come and talk whenever I’m asked,”

says Nishibori, all smiles.

He promotes these activities because he believes that the essence of

universities is to develop the next generation. “In the Hirameki Tokimeki

Science program, I have students from my laboratory guide experiments as science

communicators. For high school students, graduate students represent what they

could be in only a few years, and therefore the graduate students seem more

familiar to high school students than I do.” In fact, several students have

already entered the School of Applied Biological Science after becoming

interested in their research through catered lectures by Nishibori and other

events. One of the students under his guidance also entered the school in this

way. Nishibori looks happy when he states, “Our laboratory frequently provides

students with occasions to speak in front of others, such as at scientific

conferences. Through these efforts, our graduate students usually receive an

award or two before they complete their courses, and also easily find

employment.”

In the meantime, Nishibori has continuously requested that the audience of his

catered lectures draw a chicken. “The submitted drawings always include several

four-legged chickens! I have also found out that the majority of Japanese people

draw chickens facing the left.”

Nishibori says that he not only uses these chicken drawings for discussion

during his lectures, but also regards them as another research theme of him. “I

would like to analyze this phenomenon through control experiments. This also

makes an interesting theme for children who participate in my lectures, and

helps them recognize that science always has exceptions.”

While he unfortunately cannot keep research animals by himself, since he travels

around the world to conduct research and give lectures, Nishibori finds

enjoyment in endeavoring to improve the recognition of Hiroshima University,

where he has earned the moniker “Dr. Chicken.”

In conclusion, the interviewer asked for his message to young people: “What you

like, you will do well. Come to like many things, and study them. Hiroshima

University offers you an environment to do just that!” |

|

| |

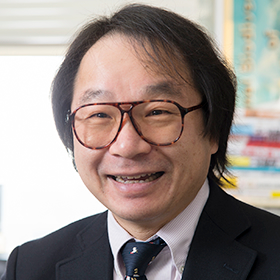

| Masahide Nishibori |

| Professor, Animal Breeding and Genetics Laboratory

January 1, 1991 – March 31, 2005 Assistant, School of Applied

Biological Science, Hiroshima University

April 1, 2002 – March 31, 2005 Assistant, School of Applied Biological Science,

Hiroshima University

April 1, 2005 – March 31, 2007 Assistant Professor, Graduate School of Biosphere

Science, Hiroshima University

April 1, 2007 – Associate Professor, School of Applied Biological Science,

Hiroshima University

April 1, 2019 – Associate Professor, Graduate School of Integrated Sciences for Life,

Hiroshima University

April 1, 2020 – present Professor, Graduate School of Integrated Sciences for Life,

Hiroshima University

Posted on Jul 14, 2017

|

| |