|

| |

|

| |

| The unique mechanism of the metamorphosis of the moon jelly is revealed at a molecular level |

| |

|

|

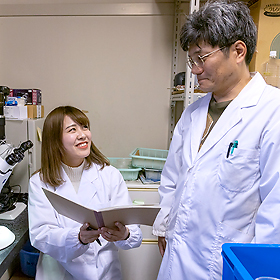

Dr. Kuniyoshi's Laboratory of Aquatic Biochemistry conducts research on aquatic organisms from the perspectives of biochemistry and molecular biology. The main project being undertaken by Dr. Kuniyoshi's research group is the study of the metamorphosis of the moon jelly.

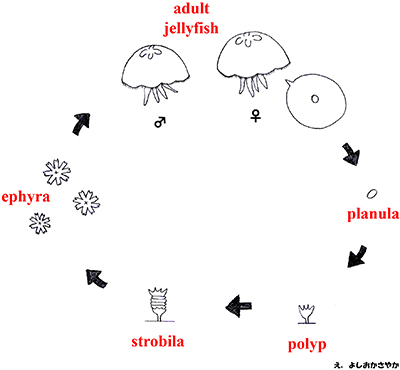

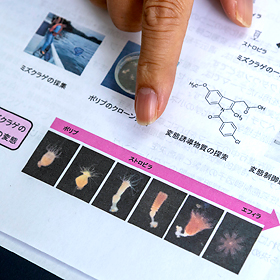

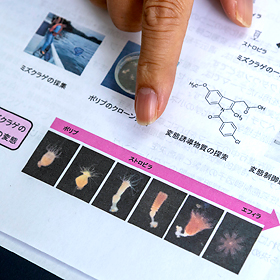

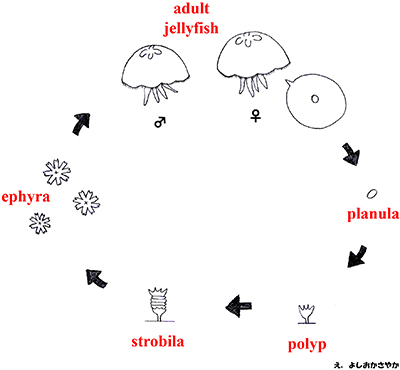

Here's the lifecycle of the jellyfish. In the case of the moon jelly, the metamorphosis takes place in the following order: fertilized egg, planula, polyp, strobila, ephyra, and adult jellyfish. Dr. Kuniyoshi explains the details as follows:

"The eggs of the moon jelly are fertilized inside the mother's body, where they develop into planulae that attach to rocks and other surfaces to form polyps. The polyps look like tiny anemones. They divide and increase in number, and when the water temperature drops in the winter, they metamorphose into strobilae and ephyrae." |

|

| |

Dr. Kuniyoshi is particularly interested in the process of change from polyps to ephyrae.

"The strobila is shaped like a stack of plates. In order for this to take place, one constriction forms at the base of the polyp's tentacles, and then another one underneath that constriction, causing the constriction to increase. The space between the constrictions becomes a segment, and eventually that one segment turns into a single ephyra, or little jellyfish."

In this way, the moon jelly repeatedly multiplies by cloning itself.

Dr. Kuniyoshi found this phenomenon quite interesting, and is endeavoring to understand the molecular mechanism of this metamorphosis. |

|

|

|

| |

His approach is a combination of molecular biology and bioorganic chemistry. Dr. Kuniyoshi's research focuses on organic chemistry, and he often conducts experiments using substances. The "substance" here is what is known as “bioactive substance.”

"When I started, for example, I wanted to find a substance that would stop the jellyfish from metamorphosing, or a substance that would induce metamorphosis under conditions where metamorphosis would not occur." By studying the mechanism by which a substance causes a change in the body when it is introduced, or the "action mechanism," we can understand which genes are working normally. That's what the search for the substance means. |

|

| |

The lifecycle of the moon jelly

|

| |

| Succeeded in discovering a bioactive substance that would induce metamorphosis in a rapidly advancing field of research! |

| |

As a result of conducting a series of researches such as identifying a bioactive substance that induces or inhibits metamorphosis and determining their chemical structure, and endeavoring to administer a variety of chemicals with a known chemical structure and seeing if anything happens, Dr. Kuniyoshi has succeeded in purifying and isolating several substances. He has also made several lucky discoveries, he says. One such lucky discovery was the discovery of how a substance known as “indomethacin” would work.

As mentioned above, polyps metamorphose into strobilae at low temperatures. However, when they are treated at low temperatures in a constant-temperature incubator, the polyps exhibit variations from one individual to another. When he experimented with various substances to see if it would be possible to promote this metamorphosis with chemicals, he found indomethacin among approximately 500 different substances. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

"I was able to use so many different kinds of substances because one of my seniors in college was working on building a library of such substances, so I was able to use them. I was really lucky," he says.

He had yet another lucky break. This indomethacin can be used to develop polyps into ephyrae within about two weeks, so the aquarium staff who have read Dr. Kuniyoshi's paper have used it and found it useful. "They need to get the jellyfish on display during summer vacation and at other times of year when there are a lot of visitors. I didn't expect it to be used like that, not at all." He was surprised by the unexpected response and said with a smile, "I think I've helped the world a little bit.” |

|

| |

His next goal is to clarify the how the segments would form in the moon jelly.

In the moon jelly, the larger polyps have more segments and the smaller polyps have fewer segments. In other words, there seems to be a rule that they adjust the number of segments according to their size, and each segment becomes constant, regardless of the size of the individual.

In addition to insects, segments are produced in the muscles and hindbrain of human beings. In insects, however, a fixed number of segments are formed, and smaller individuals have smaller segments. The segments formed in the hindbrain of humans are also created in a similar way to those of insects, but the segments in muscles are known to be created through a different mechanism.

Another unique feature of the moon jelly is the fact that the segments are formed one by one in sequence.

"The moon jelly's segments are probably made very differently from those of insects and vertebrates. I'd like to find out which molecules are responsible for the formation of those segments." |

|

|

|

| |

|

According to Dr. Kuniyoshi, there are many jellyfish researchers in Japan, but jellyfish research at the molecular level has only become more active in the last few years. "Research to determine the entire genome sequence of an organism is called a genome project, which is so advanced that a database has been created for the moon jelly. For this reason, research at the molecular and genetic levels is advancing rapidly," says Dr. Kuniyoshi. Moreover, there are not yet many studies that examine individual phenomena. Research aimed at clarifying the full extent of metamorphosis is still rare. |

|

| |

Experiment first rather than think!

Work on experiments while enjoying novelty and unexpectedness |

| |

|

|

|

One might have thought that his love of jellyfish had led him to his current research, but Dr. Kuniyoshi comes from a laboratory of organic chemistry. When he came to Hiroshima University, he assisted Professor Emeritus Susumu Ikegami, who was researching starfish. Later he worked with Dr. Yoichi Sakai of the same graduate course to study sex change in wrasses.

"Professor Emeritus Ikegami, who has retired, told me I should be free to do what I want to do afterwards. So I studied the wrasse for a while. I went to Kurahashi Island and caught a large number of jellyfish while fishing. This is what inspired me to start my current research.

Later, I started keeping jellyfish as a hobby, which turned into something like a student's research project during summer vacation, and eventually became the student's thesis research, and is now in full swing.

When asked about what makes this research so interesting, he replied, "One of the things that makes it interesting is encountering ways of life and phenomena that are so far removed from the human way of life. And there's a lot of unexpectedness, and the more research I do, the more mystery I discover. The unpredictability of the future is fascinating," he said with a grin.

And to the young people who are thinking about their future career, he sends this message.

"There's so little knowledge of other similar creatures in this field that everything we've done is new and entirely unexpected. Many people shy away from the word "organic chemistry" because it sounds too difficult. But you'll get used to it once you try it, and if you enjoy experimenting, you don't have to think about difficult things. In any case, since you are going to do something that no one knows about, why not experiment before you think? Let's not think about difficult things. And let's keep solving challenges by experimenting! You can proceed like that. It's more fun that way, and it's an approach that I think is probably the shortest way to go. Please don't be afraid to knock on a laboratory door. |

|

| |

| Hisato Kuniyoshi |

Associate Professor

Laboratory of Aquatic Biochemistry

April 1, 1994 to March 31, 1995 Special researcher at Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

April 1, 1995 to April 30, 1998 Researcher at Yamamoto Behavioral Evolution Project, the National Research and Development, Japan Science and Technology Agency

May 1, 1998 to September 30, 1998 Researcher at Riken Brain Science Institute

October 1, 1998 to August 31, 1999 Researcher at Yamamoto Behavioral Evolution Project, the National Research and Development, Japan Science and Technology Agency

October 1, 1999 to October 31, 2000 Postdoctoral researcher at University of Toronto

November 1, 2000 to March 31, 2002 Assistant at School of Applied Biological Science, Hiroshima University

April 1, 2002 to October 31, 2006 Assistant at Graduate School of Biosphere Science, Hiroshima University

November 1, 2006 to September 30, 2012 Lecturer at Graduate School of Biosphere Science, Hiroshima University

October 1, 2012 to March 31, 2019 Associate Professor at Graduate School of Biosphere Science, Hiroshima University

April 1, 2019 to present Associate Professor at Graduate School of Integrated Sciences for Life, Hiroshima University

Posted on nov 25, 2020

|

| |