Elucidating aggressive behavior in chickens

to make them easier to raise and more productive

In many locales in Japan, chickens are raised for regional promotion by crossing Japanese native chickens, mainly Oh-Shamo (Japanese Large Game), with commercial breeding hens of foreign origin. Their offspring are called jidori, and feature a special flavor unique to each locale. However, jidori chickens pose a serious problem to poultry farm managers: they are extremely aggressive because of the traits they inherit from their male parents, and violently peck one another when kept in a group.

To solve this problem, Associate Professor Shin-Ichi Kawakami’s group is carrying out research into the brain mechanism of aggressive behavior in chickens, which remains largely unknown, under several themes as follows:

1.Experimental reproduction and quantification of aggressive behavior in chickens

2.Elucidation of the mechanism of androgen (testosterone)-induced aggressive behavior in chickens

3.Identification of the chicken’s brain loci activated by aggressive behavior

4.Exploration of brain genes regulating aggressive behavior in chickens (aggressor genes)

Prof. Kawakami explains how this research began:

“Humans have captured, tamed and domesticated wild animals, eventually succeeding in using them as livestock by empirically selecting and breeding easier-to-raise, that is, less aggressive, individuals over a long period of time. But some livestock animals retain high levels of aggressiveness even today. Our research has revealed that chickens in particular, not only Japanese native breeds such as Oh-Shamo but also commercial laying hens, are highly aggressive.

“Aggressive behavior is an instinctive trait that animals have in order to obtain limited resources (such as food, mating partners or territory). It’s essential for them, but excessive aggression can also reduce livestock productivity. So some countermeasures must be found. We have decided that, in order to do so, first of all it is essential to elucidate the brain mechanism of aggressive behavior. This is how we started our research.”

Experimental reproduction of aggressive behavior in chickens

to make it possible to identify it and use chickens as a model organism

According to Prof. Kawakami, chickens are essentially highly aggressive. They would be one of the most suitable species to serve as model organisms for research into aggressive behavior. However, they have not been used significantly for this purpose. One major reason is that it has been impossible to distinguish pecking for aggression from those for communication between individuals.

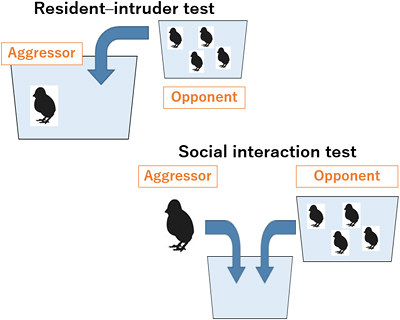

To overcome this obstacle, Prof. Kawakami’s research group observed two groups of chickens, individuals reared in isolation (highly aggressive) and those reared in a group (less aggressive), to study the attacks (and counterattacks) of aggressors and opponents. By comparing these actions, the researchers demonstrated that it is possible to identify peckings by aggressor chickens as constituting either aggression or non-aggressive communication. Based on such findings, the research group selected and improved two behavioral tests to better suit their original research using chickens: the resident-intruder (R-I) test and the social interaction (SI) test.

Schematic illustrations of resident–intruder test (R-I test) and social interaction test (SI test)

Schematic illustrations of resident–intruder test (R-I test) and social interaction test (SI test)

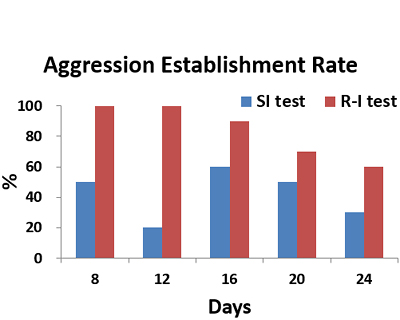

To compare aggressiveness of the chicks, we calculated the aggression establishment rate, which is equal to the number of aggressors showing high aggression per total behavioral trials. The criterion of high aggression was defined as the total aggression frequencies (TAF), where aggressors showed more than 30 times of TAF and the opponents did less than one-third TAF of aggressors.

To compare aggressiveness of the chicks, we calculated the aggression establishment rate, which is equal to the number of aggressors showing high aggression per total behavioral trials. The criterion of high aggression was defined as the total aggression frequencies (TAF), where aggressors showed more than 30 times of TAF and the opponents did less than one-third TAF of aggressors.

Prof. Kawakami explains:

“The R-I test makes use of animals’ habit of marking their territories. It took us almost two years because it was extremely difficult to experimentally reproduce situations of aggression with chickens. The SI test is based on the fact that, in the case of a species that habitually flocks, individuals become extremely aggressive if they are intentionally reared in isolation.”

The research group also conducted an experiment to examine the correlation between testosterone and aggressive behavior, finding that testosterone may be used to make aggressor individuals even more aggressive during an SI test. This was conducted by subcutaneously implanting a testosterone-filled silastic tube (T-tube) in castrated roosters and examining how the changes in the blood concentration of testosterone were related to aggressive behavior.

“These behavioral tests have enabled us to use chickens as model organisms, which had rarely been used in research into aggressive behavior in the past. Moreover, it is now possible to use younger individuals (chicks from eight days of age) in the behavioral tests that we have improved because they do not require mature chickens. This means that research can be further accelerated.”

A scene of the experiment

A scene of the experiment

Aggressive behavior in chickens is programmed in their brains.

What genes are involved?

Prof. Kawakami is currently focused on Themes 3 and 4 listed above. In other words, he is looking inside the chicken’s brain.

“There are two types of animal behavior: acquired behavior, which animals learn after birth, and innate behavior, which they do not learn but are born with. Aggressive behavior is believed to be an innate or instinctive behavior and is genetically programmed. That is to say, we think it is regulated by a set of genes. It is extremely interesting that certain animal behaviors are genetically controlled. Starting with this research into aggressive behavior and other instinctive behaviors, we are hoping to eventually expand the scope of our research to cover the mechanism of acquisition of learned behaviors as well.”

Regarding the question of which part of the brain is activated when aggressive behavior occurs, it is already known that it is the part called the hypothalamus, which is the center of intuitive behavior.

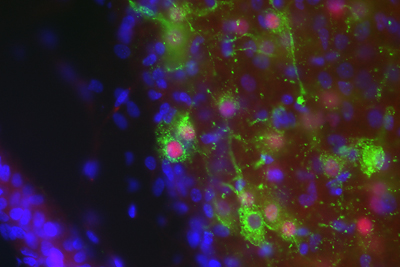

Prof. Kawakami says, “When neurons become active, the gene c-FOS, which is in the category of immediate-early genes, is expressed in response and becomes the indicator of neuronal activation. Since we already know that c-FOS is expressed in the nucleus as nervous cells become intensely active, we use this knowledge in trying to pinpoint which part of the hypothalamus is involved in aggressive behavior.”

At the same time, the research group is also continuing the exploration of brain genes that regulate aggressive behavior. Scientists are currently selecting candidate genes from among exhaustive analytical data on genes to conduct functional analysis. There are several approaches to this process, including one using a microarray. To inhibit gene function, they use a method called “RNA interference (RNAi),” that is, interfering with the function of a given gene to see if it is essential for aggressive behavior.

Verifying brain loci involved aggressive behavior using c-FOS expression as an indicator: activation of neurons containing candidate genes during aggression

Verifying brain loci involved aggressive behavior using c-FOS expression as an indicator: activation of neurons containing candidate genes during aggression

Prof. Kawakami says, “We haven’t reached the stage of gene identification yet, but it’s highly likely that new candidate aggressor genes will be selected from our research. I’m hoping to focus on my research while considering all possibilities and eliminating preconceived notions as far as possible.” He is determined to pursue his research with serene concentration.

Opened on September 21, 2021

Opened on September 21, 2021